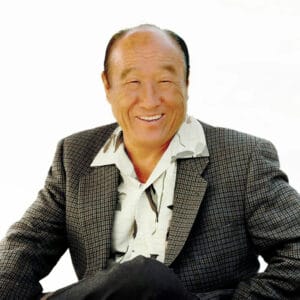

THE OPTIMIST – Sun Myung Moon (January 6, 1920 – September 3, 2012) was a Korean religious leader, also known for his business ventures and support for political causes. A messiah claimant, he was the founder of the Unification Church movement, its widely noted mass wedding ceremonies, and the author of its unique worldview explained in the Divine Principle. He was an anti-communist and an advocate for Korean reunification, for which he was recognized by the governments of both North and South Korea.

In any case, the Rev. Moon − much in the tradition of Christianity − was not uncertain regarding what he and most other monotheistic people of faith call God’s will. For Unificationists, in particular, the meaning of life boils down to the postulate that God created Adam and Eve in his image and as his objects of love. Humans exist to please God.

The New World Encyclopedia, publicly launched in February 2008, sports a most informative webpage on Sun Myung Moon.

Michael Mickler, a professor at the Unification Theological Seminary in New York, published the book “The Unification Church Movement.” in December 2022. It is not a critical expose of the Unification Church movement, but rather an account highlighting the leading personalities, organizations, and circumstances which facilitated the UCM’s rise, its present challenges, and future development.

The teachings of the Unification Church movement are a bit unconventional or unorthodox but still fall squarely within the provenance of the larger Judeo-Christian tradition. For Christians as well as Unificationists, there than stand a God, Original Sin, an immortal soul, and eternal life in a Spirit World as the hypothetical pillars of belief.

And if God created humans in ‘his’ image, and if humans do have a bodily-death surviving soul, and if eternal life in what is called a Spirit World is not just wishful thought, then we have all the ingredients to conjure up a wonderful meaning of life. So one might think. Be good today, and await your redemption as promised later than sooner. Traditional Christian and Unification theology both advocate a system of delayed self-gratification − on a truly grand scale.

I have become skeptical about foundational Christian assumptions leading to interpretations of the meaning of life. The contingent doctrine of sin and salvation is especially consequential in playing on people’s sentiments regarding immortality.

The Root of Anxiety

English writer, speaker, and self-styled “philosophical entertainer” Alan Watts had a few things to say about the root of anxiety. Watts is remembered for interpreting and popularising Japanese, Chinese, and Indian traditions of Buddhist, Taoist, and Hindu philosophy for a Western audience.

Maria Popova, the author of the magnificent The Marginalian, highlights in several brief essays some of the thoughts of Watts. Watts, she writes, argues that the root of our human frustration and daily anxiety is our tendency to live for the future, which is an abstraction. What keeps us from happiness, Watts argues, is our inability to fully inhabit the present.

Unificationists, like many people of faith, are especially prone to live for better prospects in the far future. It has always amazed me how the human mind is able to go to extremes by positing immorality.

The need for living in the presence has, over time, spawned a substantial cottage industry of writers and speakers. This seems to be a reversal of things as I thought that living in a strong perspective of a just future was a way of coping with the anxieties arising from living in the unjust present. Strange.

Immortality

The desire for immortality begs the question of what the meaning of life will be in the Spirit World, that is, for an otherworldly, immaterial human existence in all of eternity. That is a long time! Years ago, I read Swedenborg, Borgia, and others on the Spirit World but remember no good answer to that question. Some authors suggested that for a living human to experience the Spirit World is a blissful, meaningful, and life-changing experience. Yes, but that momentary and initial excitement needs to be contrasted with the possible dread of having to exist for eternity. But my most pressing concern is that of the likelihood of God continuously favoring humans, or whatever we might become via eternity. Why should we believe that humans will be favored in all of eternity − what is it that makes us so significant, so eternally lovable to a supreme being?

Singing Hosanna for trillions of years with no end in sight? Angelic underlings to serve us manna repetitively every day? Slowly meandering from a lower sphere to a higher one, as some spiritualists suggest? Finding your relatives on the way? Losing our very self on the way to merging into the Divine? I would be far from the first to warn of existential boredom. Other folks think that humans can be made to enjoy what dreams may come, though. However, I just do not see how humans could be the ‘end of all ends’ worthy of God’s patronage for all of eternity. Unificationists do not convincingly address this concern of the perpetual end of ends.

https://aeon.co/essays/how-heaven-became-a-place-among-the-stars

Most people of faith might just shrug off that looming worry, saying “Who cares? I keep believing and thus earn my spot in Heaven. What could be more rewarding?” That is an astonishingly short-term perspective. Not so for the believer, though. He or she is infatuated by the prospects of immortality but cannot conceive the notion of eternity. Really, who can?

God and Faith

Existential philosopher Soren Kierkegaard spoke of the ‘leap of faith,’ of leaving doubt behind no matter how irrational one’s beliefs and subsequent behaviors appear to become. Philosopher and psychologist William James spoke of the right to believe, that it is OK to abandon oneself to believe while empirical evidence of the Divine is still only forthcoming (or not). The act of believing in the Divine may then actually evidence the Divine, without which it would not be so certain.

Kierkegaard’s approach was never available to me, being a bit of a ‘doubting Thomas‘ to begin with; and James’ approach, a more reasonable approach, does not work for me anymore. Rev. Moon’s exuberance or optimism regarding God’s will and love could not make up for my sense that God’s benevolent involvement in this frail world full of human folly was not forthcoming. I expected more cooperation from God.

Pantheism is the doctrine that the universe conceived of as a whole is God and, conversely, that there is no God but the combined substance, forces, and laws that are manifested in the existing universe.

The Rev. Moon was not a pantheist, but a classical monotheist. I think that he gave us, not unintentionally, the impression that he talked daily with God. For the Rev. Moon, God must have been an imminent person.

I mean, how much longer are the rest of us to wait for the self-revelation of God? In perpetuity, here on Earth? What is preventing him from coming out? I know that theologians have all kinds of rebuttals to my quarrels. But for me, the time has run out for their hypotheticals.

German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche declared that God is dead. But God need not be dead − what if he just lost interest and moved on? It seems that even the Rev. Moon, while undoubtedly trying very hard, could not tickle God’s fancy that much.

The Soul

And for the soul? I have looked into a mirror for decades and recognized a lot of items in myself, such as St. Augustine’s cravings, Descartes’ self-conscientiousness, and the Freudian Id. But I found no soul, no spirit, no immaterial substance transcending my skin and flesh and bones. There just does not seem to be anything but flesh and bones under my skin. Flesh and bones under my skin as the neurobiological ground of my experience of consciousness and agency. I am not a Cartesian Dualist anymore.

However, I found a bit of divinity in myself. A divine-human? Well, perhaps, in a metaphorical sense. A divine animal? That’s more like it. Whether or not ‘divinity’ is an illusion, or constructed notion, and as an adjective, a projection is further debatable. But I do have a ‘better self,’ it seems.

Now, quantum mechanics may one day tell us more firmly about entanglement, of Einstein’s ‘spooky action at a distance,’ of things beyond skin, flesh, and bones as we know them. Will that ever amount to evidence of a mental substance or immaterial soul?

Jungians view the soul as a faculty of the mind or psyche that discerns meaning. I can live with that explanation.

I have also wondered about strange and unexplainable phenomena like that of seances, e.g., the stuff of the supernatural. There are people more spiritually open or gifted than me. And I have met people, other than the Rev. Moon, who sported an extraordinary aura of a sort of commanding gravity or magnetism. They had ‘an air’ about themselves, I could sense it. A soul? I do not know. For me, the cup is not half full enough to entertain the notion of an everlasting immaterial soul as something other than wishful thinking. Is the desire for immortality not natural?

Kierkegaard’s and James’ arguments in favor of faith go only so far. However, their arguments seem to apply to at least the conundrum of marriage. One does never know if their love will last, yet we marry. The show must go on, despite us not knowing who we will be in some 10 years, or who the other will be and marry today. For this author, the best of ancient wisdom will do, but not hypothetical theology.

Here is a good read about the soul – https://aeon.co/essays/why-are-most-of-us-stuck-with-a-belief-in-the-soul

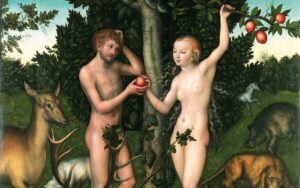

The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve

The narrative of the Fall of Man, of Adam and Eve’s disobedience to God’s commandment not to eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, and especially the subsequent doctrine of sin is just that: a mythical rationalization to help humans deal with the fear of death and the tragic sense of life. The fear of death, according to philosopher Hannah Arendt, was what caused Augustine to finally convert to the early Christian faith and animated him to reflect in his writing on his experience of life, love, and death. In the end, Augustine found it proper to blame most all misery on the theological construct of sin. Few have laid out the theological foundations for Christianity as much as Augustine.

However, Christian theories of sin and salvation and/or Unification theories of original sin and restoration have so far not been able to satisfactorily address and certainly not solve the problem of human alienation and relationships. I am not the only one to think so:

“In the future, the Divine Principle will need many updates. What I mean is that theories from the Completed Testament Age do not suffice.”

Mrs. Hak Ja Han Moon

March 16, 2018

Famicon 2018, IPEC, Las Vegas, Nevada.

I wonder if Mrs. Hak Ja Han Moon, the Rev. Sun Myung Moon’s eternal spouse, had the same suspicions in mind when she said what is reflected in the above quote. She, apparently, thinks that the Divine Principle is full of theories − perhaps only containing a grain of truth. Astonishing!

I am not a Bible quoter. I do not believe that the Bible is the literal word of God. But just to shore up my point of view, here is Genesis 6:6 − pretty damning or not?

“The LORD was grieved that he had made human beings on the earth, and His heart was deeply troubled.”

Genesis 6:6

What is your theory? Here is mine. Adam and Eve did not live up to God’s expectations. Apparently so, if one wants to go along with the utterly hypothetical Christian narrative. But who is to blame for that? “Not God,” say most people. That, too, is astonishing! Ordinary people as well as literates hold God faultless because they need and wish him to be faultless. Anything less than that would sow nothing but confusion among their kind.

God knew that he made a mistake. Why do Christians only blame Lucifer, Adam, and Eve for all the troubles in the world? Rev. Moon blamed Lucifer, Eve, and then Adam for it − in that order, but held God faultless just as the Christians do. Perhaps the Rev. Moon desired to be God’s dramatic rescuer while also personally trying to benefit from capturing the minds of the masses via the blame and shame game established by Christianity.

God made the mistake of poorly parenting his creation, the angles and humans, − that is what I have come to think after all. This is, however, a difficult hypothesis or assumption for most people to take. “God made cardinal mistakes?” Oops, that would undermine the whole psychology of the Christian religion and pull the carpet from underneath the faithful. Rev. Moon, perhaps, did not want to go that far in his already unorthodox-enough teachings.

“The truth will set you free!” Can’t remember who said that, but Unificationism has not arrived yet, definitely not. Unification movement members are still in Christian chains.

The affairs of humans are transactional affairs that also call for a theory of social dynamics. Unfortunately, Unification theology is derived largely from hypothetical considerations of individual motivations and subsequent failings of a few mythical human ancestors as well as non-human beings (angles), ignoring most all anthropological insights into human living. As the late Dr. Young Oon Kim, Professor of Systematic Theology at UTS has pointed out in her book on Unification Theology, there is little to no consensus among theologians as to what Original Sin really is.

Now, if Adam and Eve are mere metaphorical characters, and if sin is a mere metaphor to explain or justify shame and guilt, then the inherent dogmatic aspect of the Unification movement’s teachings called the Divine Principles is a mere ruse. Yet, these dogmas were utilized by Unification leaders to compel members, including themselves, to engage in severe self-sacrifices − in living for the sake of others − to an inhumane degree bordering on abuse. Not that it is unique to Unificationism, it is part and parcel of of the history of Christianity.

Miguel de Unamuno gives a richer, more convincing exploration of human affairs, of human anguish (watch this brief intro if pressed for time) in his philosophical thoughts on life, death, adversity, consciousness, religion, and the personal achievement of authenticity, published as a book entitled The Tragic Sense of Life. But it is not the silver bullet of understanding that so many simple folks prefer.

It seems that anguish from a fear of death underlies, as an animating sentiment, most all monotheistic religions. Both the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and the German philosopher Martin Heidegger also had interesting things to say about the human condition, but their thoughts are perhaps too complex to innumerate in this post.

The experience of one’s own alienation from self and others is perhaps the strongest clue to the mystery of why so many people tend to become religious. The narrative of the Fall of Man seems to hit a chord with many of these folks. Does our alienation stem from the disobedience of our primal ancestors Adam and Eve? That hypothesis necessitates a very long and therefore implausible chain of cause and effect to arrive at an explanation of human alienation. And a lot of people do not feel alienated, that is, sinful or fallen, etc. It is not the universal condition that Christians wish to project on everyone.

I have come to favor Lacan’s explanation of the Mirror Stage, a narrative of emergent self-consciousness derived from Hegel’s and Kojeve’s writings, as a more sensible explanation of existential, human alienation. Some things just do go wrong in many people’s childhoods and to various degrees; a good life is not a slam dunk.

The late Rev. Moon, however, seemed to be fearlessly optimistic until his last hour. His teachings incorporated the Christian narratives of Adam and Eve and their Fall from grace, with an emphasis less on the disobedience of authority and more on improper sexual behavior. A rather behaviorist doctrine of salvation followed, called Principles of Restoration. Submission to a self-impaling, pessimistic fate was not in the Rev. Moon’s teachings. He probably did not mean to create any dependencies on his authority per se, either, as some forms of Catholicism intentionally engendered.

Antithetical to all the many naysayers in this world, his distinct appeal of optimism might outlast all criticism of self-aggrandizement directed at him for his attempts to reach out to his suffering God. His was a God not anguished by fear of his own death, but by the loss of his children − also a kind of death.

The Rev. Moon tried to comfort his God. A radical idea to most, for sure. If God is in need of comfort, then perhaps what else? Is God then still almighty?

Lasting Appeal

Despite having chimed in with traditional Christians in promoting God, the soul, and immortality, the late Rev. Moon still has a lot of appeal for me as well as for many others. He was great at tantalizing prospects and members, that is, at exciting folks by promoting a desirable vision of hope that nevertheless remains or is made difficult or impossible to obtain. Of all the messiahs that have come and gone by now, he probably was the best. Many more will come forward over time, none perhaps to best him.

The Rev. Moon was an absolutist. How can one best absolutism? Many folks admire absolutists. That is what people wanted when they joined the Unification movement: absolute faith, absolute truth, absolute obedience – that sort of thing. True love, which is unconditional love. Love for the unloved or even the unlovable. Absolutism and truth and love, if asserted constantly via rhetoric, attract a certain kind of folk.

Moreover, he was an accomplished one-upmanship master. One-upmanship is the art or practice of successively outdoing a competitor. He could not stand being subjugated or put down by anyone. For him, there was always a way out of a nasty predicament or condition, and that was the way of ‘living for the sake of others.’ Nobody would or could outdo him in this regard, so he told himself.

No matter how imprecise his theological explanations were, the Rev. Moon promised in his speeches and testified with his lifestyle to the absolute certainty about the meaning of existence. He could spin his yarn for hours and hours of no end. As such, he mystified people more than clarified the pressing issues needing explanations. As said before, he spoke under the assumption that the listeners already believed, or were willing to believe in a Judeo-Christian God. He did not really demystify the Fall of Man, that is, the story of Adam and Eve.

Angels? Yes, of course. Who are they and where did they come from? Well, we’ll figure all that out later. God gave Adam and Eve one injunction. That’s it? Is that what good parents do for their children? We do not deserve to understand details? “The time will come when I will tell you more,” is said to be already Jesus’ words. When will that time come if not during the Second Coming of Christ? A high level of uncritical acceptance of religious assumptions (doctrines) seems to be ingrained in many Unificationists.

Some members of his attending entourage would fall asleep, but the general audience of members in attendance would not dare to. How could someone not be ‘true’ if being willing and able to pour out his heart and soul in 12-hour-long speeches about God and human affairs? Most followers became absolutely loyal to this absolute king and his queen.

I have recently read William James again and am pragmatic about religion now. Religion has done and still does some good. Re-reading Will to Believe has helped me to open fresh perspectives, again. Do people of faith and even agnostics not seek certainty as a most precious good? Especially certainty about the prospects of a good life? Who gets inspired by hearing, from the likes of Camus or Sartre, that existence is absurd?

The Rev. Moon’s appeal was broader than being a man of traditional faith in the vein of even Kierkegaard’s conceptions. Still, holding and communicating in all sincerity an unwavering belief in the benevolence of God’s will, the Rev. Moon had not the hallmark of a socialist reformer but a charismatic leader of ordinary people. I know. He spoke for hours to us about his Korean brand of the Judeo-Christian tradition, intensely unguarded and unrehearsed and with unending energy and hope. And he acted in no uncertain ways to produce a few heroic achievements.

He appeared not to be a blockhead, either. His certainty and originality were acts of natural disposition, mood, attitude, and faith, possible only because he also spent countless hours in contemplation.

Those who believe they believe in God, but without passion in the heart, without uncertainty, without doubt, and even at times without despair, believe only in the idea of God, and not in God himself.

Miguel de Unamuno

This doubt, this despair, he never showed in public., however. He always chose to rather let his optimism, his unbridled passion, and certainty, shine through.

And therein perhaps lies the genius of the Rev. Moon. His life script, his mood, and his attitude in life garnered him a large audience. Following him absolved many devotees of the unwanted responsibilities of figuring out for themselves the meaning and purpose of life. “Philosophy and theology,” I was told by a Unification pastor a few years ago, “get too complicated too soon.” Fair enough. The Rev. Moon showed that life is worth living as he lived a worthy life. A Ph.D. is not required.

“A detached man, who knows he has no possibility of fencing off his death, has only one thing to back himself with: the power of his decisions. He has to be, so to speak, the master of his choices. He must fully understand that his choice is his responsibility and once he makes it there is no longer time for regrets or recriminations. He decisions are final, simply because death does not permit him time to cling to anything. . . . The knowledge of his death guides him and makes him detached and silently lusty; the power of his final decisions makes him able to choose without regrets and what he chooses is always strategically the best; and so he performs everything he has to with gusto and lusty efficiency.

“A Separate Reality” Further Conversations with Don Juan, by Carlos Castaneda, Page 183

Less decisive folks, those perhaps with few good prospects in life or with actual grievances of one kind or another flocked to the Rev. Moon, for salvation or even only a hands-up. Not a first, such a dynamic occurred some 2,000 years ago at least once before.

Of course, others − those perhaps with more curious, inquisitive, and creative minds − were not as quickly pacified as they also joined. I recognized some fairly capable leaders emerging in the Unification movement. That is, people from all kinds of walks of life joined the Rev. Moon for their intimate reasons. Again, the Rev. Moon had a rather broad appeal, the least of which was not his demonstratively vital relationship with his last chosen wife Hak Ya Han. They seemed to enjoy a rather game-free intimacy, or intimacy based on playing complementary games (the only begotten son or daughter or OBSD) with each other. It is hard to say as I am not an early disciple who shared living quarters with them. In any case, their intimacy became the envy of many a jaded folk who eventually joined the movement and stayed.

At the same time, he became the envy of those who might have felt that he was encroaching on their turf of social glory. In the end, the Rev. Moon is not unappealing in these days of the ‘woke and cold’ liberalism on the political left and the jealous protectionism of theological orthodoxy.

The Rev. Moon passed away quietly in his Korean homeland in 2012 at the advanced age of 92. His flesh and bones were cremated soon thereafter, his life undoubtedly a heroic achievement. Did his God fail him?

Living for the sake of others

Regarding the question as to the value of life and living, what can we still read into the optimism or humanism of the late Rev. Moon?

Well, he was not a man who withdrew from this troubled world into an ascetic or esoteric or academic or comic or plain uncontroversial lifestyle. His interpretation of God’s will embraced the act of fully living in prosperity under the motto of “living for the sake of others.” He did so with drama and abandon, in effect summoning others to do so as well. The tragic sense of life, as perhaps looming in many of us, was not in the open in the Rev. Moon. He dared any devil and never resigned.

Cynics like Mark Twain may have pointed out that this motto is little more than exploitative posturing − in fact only to say that “you now live for my sake.” Fair enough. But skeptics like William James may have retorted that a listener would have the choice to give that motto and its bearer more of a benefit of the doubt. It isn’t a phrase that the Rev. Moon coined, it is part and parcel of time-tested Taoist and Confucianist ethics.

Was ‘living for the sake of others’ a mere means to some other, more self-oriented end for the Rev. Moon? Or was it the proverbial end for him, period? That is hard to say without giving away a bias. He certainly tried to earn his credentials.

Rev. Moon’s level or standard of self-denial, nevertheless, did not reach the voluntary amplification of that of martyrs such as the apostle Peter who asked to be crucified upside down. That is, ‘dying for the sake of others’ is not pleasing to God and wasn’t in the cards that Rev. Moon read.

Yet, the Rev. Moon was not an avoidant as he got himself tortured during his youth in North Korea for his anti-communism, and surrendered to be incarcerated at Danbury prison for petty tax evasion. And he did not go on a hunger strike during his tenure at Danbury to contest his sentence.

He surely could take a good beating and still come back with a vengeance. In his self-chosen way, he did assume a lot of obligations and tried to deliver on them. He also granted himself and others a lot of privileges.

His Taoist / Confucianist interpretation of a Christian God’s will − as exemplified by the motto ‘living for the sake of others,’ had an emphasis on the word ‘living.’ The Rev. Moon lived an immersive life and summoned others to emulate this glorious attitude. Any rendered sacrifices as per living for the sake of others, small or substantial, would expectedly be made whole and worthwhile by others reciprocating as much − if there were those. Not all followers got that memo.

The One-up Maneuver, or Taking the Moral High Ground

‘Living for the sake of others’ was the overt motto or script of Rev. Moon’s life. But the Rev. Moon also had a method to the madness with the aim of rescuing his God.

I prayed in tears for the presidents and top-level people. Through my prayers, I would have them indebted to me. And they are in the position to repay me. If they don’t repay me, heaven will snatch away what they have and give it to us.

Way of Tradition, vol. 4 on Leadership:99, p. 333

Here is a good lead-in to the issue. Human beings, says French philosopher Alexandre Kojève, are defined by their desire for recognition, and it is a desire that can be satisfied only by another person who is one’s equal. In this reading, Kojève unfolds a multi-step process: two people meet, there is a death-match, a contest of the wills between them, and whoever is willing to risk their life triumphs over the other, they become the master, the other becomes a slave, but the master is unable to satisfy his desire, because they’re recognized only by a slave, someone who is not their equal. And through the slave’s work to satisfy the master’s needs, coupled with the recognition of the master, ultimately the slave gains power.

https://aeon.co/essays/the-philosophical-legacy-of-alexandre-kojeve

By living for the sake of others, overtly or covertly, one generates indebtedness and reclaims the moral high ground and a certain authority. This is the ultimate one-up maneuver, as it puts everyone else at least one down. No need to be a tyrant, a dictator, a king, an obvious dominator, or something like that. Acting out this cosmic one-up maneuver is much more elegant than, let’s say, establishing authority via enforcing mere parental injunctions.

‘Living for the sake of others,” can be done quietly, in a way that still gives the liver a lot of pleasure. ‘Living for the sake of others’ need not be the covert method of a person wanting to become a rescuer. It can just be the method of living of an ordinary person. Using this method to become the rescuer of God may actually spoil the endeavor as it will split loyalties. One will be loyal to his or her god, and as such most likely throw a lot of people under the bus.

Unificationists typically label that behavior as expressing God’s love, or as the Biblical loving your neighbor or your enemy. Actual liking of the recipient of that attention is not required. Pity will do, and so will empathy or even parental injunctions, scorn, and contempt.

It is a lonely path to walk at times, especially at the beginning of a ministry. I suppose that Jesus had already discovered that, and the Rev. Moon as well as luminaries like Gandhi, Mother Theresa, and MLK figured out how to follow that script. For the Rev. Moon, any and all personal and public activity had to be lived sincerely with utmost devotion and in even the most minute detail. From what I can tell, that is how he lived intertwined with his God, not in a monastery but among all people.

I wonder if the Rev. Moon overdid it a bit by adhering to his Principles of Restoration too literally. Most of his own children were seemingly neglected during their upbringing by him − if not thrown under the bus, in favor of ‘loving the enemy.’

In a stunning reversal, his surviving wife, Hak Ja Han, nowadays emphasizes that a loving heart is more significant than a cold principle. Yes, one might say, the times are a’changin. But the damage is done.

Fighting the Evils

The movement the Rev. Moon started was not about caring or about handholding in the first place. It was about resurrecting an ailing God who had lost his children − by fighting the enemies, the evils within and external to the self. Some people joined by making the Kierkegaardian ‘leap of faith,’ that blind leap, that close-your-eyes kind of moment or series of moments where, in the face of insufficient evidence, you somehow trust God with your life anyway. There was love to be had in the fighting.

Others, like me, joined by way of exploring the Jamesian ‘right to believe,’ that is, by trepidatiously crawling over that raggedy straw bridge across the chasm and finding out that they could. That is, we could participate in making God’s creation project worthwhile. There was glory to be had in the fighting.

Of course, in life, there is no clear demarcation between these two or even other approaches.

However, it is ironic that the effort to restore Adam and Eve was taken by too many too dogmatically − rather than pragmatically, as with a grain of salt so to speak. Sacrifices needed to be made. Some of those born into the movement as 2nd. generations say that they experienced traumatic circumstances growing up. It is always hard for a leader to control what followers, and followers of followers, will do. But the Rev. Moon could not demonstrate a sustainable example of parenting, of child-rearing himself. He must have had priorities, and there was a lot of persecution that created havoc in the lives of his offspring. It is said that the Puritans, after arriving for a new start here in the New World, lost their second generation to unfortunate dynamics as well.

Prosperity

However, the beauty of this ancient motto of ‘living for the sake of others‘ is that it holds up fairly well regardless of this monotheistic religion. The notion of reciprocity, as advanced by this motto, may help Western culture to find an antidote to the extreme individualism, the ‘I, me, and myself’ attitude that seems to eat away at the fabric of modern society!

Some Christians nowadays live by what is called the Prosperity Gospel. It isn’t that different from what the optimist Rev. Moon came to live by in small-town Korea long ago, and what he since has summoned others to do as well.

Most people, myself included, do not have the energy, pep, courage, and determination to match the moxy of a Rev. Moon. I admit my own middling disposition. Self-deprecating as this statement may be, it may also be true as an honest kind of reality check. At the same time, I still find myself picking up pieces of the gauntlet he threw in front of humanity.

The well-known phrase “Lead, follow, or get out of the way,” is confronting as much as the Rev. Moon himself was. He has his fair share of detractors, some are former members who likely joined out of naïveté, while many others just quietly got out of the way.

Now it is not easy to get caught up in the Unification Church movement, but it happens to some folks – for whatever reasons. There are benefits for ‘diamonds-in-the-ruff’ who are perhaps lonely, unloved, under-challenged, unlovable, overlooked, etc. I mean, why do people put themselves at risk and join the military or climb Mt. Everest? Why do people go into immense depth in order to obtain a college degree from an ivy-league school?

Is life worth living

Is life worth living? “Absolutely,” would the Rev. Moon have said. I am sure that he would have said that, and I add that living a worthy life − after all − comes unfortunately not cheap. One better makes some money to live and not die for the sake of others.

Why is it preferable to be wealthier than poorer? Well, if one is poorer, the one thing a person could bring to the reciprocating table would only be him or herself or an unsuspecting offspring in the function of the proverbial ‘sacrificial lamb.’ And that, for the person having to be making living sacrifices repeatedly, would not be much of a sustainable, worthy, and fulfilling life − I presume.

However, the one trick that seems to be working for people of all kinds of persuasions, rich in wealth or poor in sacrifice, is to become indispensable to others. One’s luck or fate may turn for the better by becoming indispensable to others − even though one may also become the target of envy or jealousy.

Living for the sake of others is a sure way to indispensability. And being or becoming part of a community of such like-minded folks can be beneficial. For me, the late Rev. Moon remains one of a few Asian sages in human history.